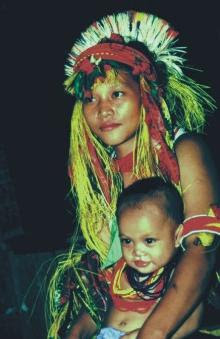

Dayak Tribe

Dayak is a name of tribes that identifies the various indigenous peoples on the island of Borneo by the Indonesian part known as Kalimantan. They are divided into about 450 ethno-linguistic groups. Despite some differences, these group share physical features, architecture, language, an oral tradition, customs, social structure, weapons, agricultural technology and a similar outlook on life.

Dayak population estimated at about four million spread over the four Indonesian provinces in Kalimantan / Borneo, the Malaysian territories of Sabah and Serawak and Brunei Darussalam. In Sabah, the Dayak are known as Kadazandusun.

In the past, anthropologists described the Dayak as the "legendary natives of Borneo" who lived in longhouse and engaged in head-hunting. Today, they form a small minority, the loser in an era of swift change and modernization.

The original Dayak identity their cultural, economic, religious and political life has been preserved through their oral tradition. Experts agree that there are many basic affinitives in the legends of the various Dayak groups. Sadly, though, all the original elements of Dayak life as described in the legends have suffered significantly from external elements.

Modern Religions

Christianity greatly affected the status of legends among the Dayak groups. The legends, which were recited during rituals, were dismissed as animistic. The Christian converts deem adherents to the traditional religion primitive and obsolete. The doctrine was spread through schools and sermons in the villages. In Central Kalimantan, people call it the "obsolete yeast" or "emptying glass" policy. Anthropologist J.J. Kusni concludes in one of his books that the propagation of Christianity amounts to the conquering of the Dayak.

The Christian proselytizers shouldering what they call ‘la mission sacre’ of civilizing the savage peoples see the Dayak culture as ‘obsolete yeast’, worth disposing. The ‘obsolete yeast’ concept tends to drain the Dayak of their culture and fill them out with new values," says Kusni. The policy was exercised not only in Central Kalimantan, but also in East, West and South Kalimantan. Further, Christianity was considered as a savior and a symbol of modernization. The impact has been great. The Christians are uncomfortable attending funerals and weddings of pagans.

In a West Kalimantan village, used as a base by a Christian mission, posters are plastered all over the place to intimidate Dayaks from practicing their cultural traditions. A poster in illustrates a path branching in two. The left is "the road to hell", with a picture of a ritual at the end of the road. The right is "the road to heaven", with a picture of modern life is seen at the end of the road.

Lifestyle

Before the 1950s, the Dayak peoples lived in communal longhouses. Today, longhouses are rare in Kalimantan. Their disappearance in turn affects the process of preserving the social, economic, cultural, and political values of the Dayak. Before, children were taught the basics, including the legends. Before going to bed, youngsters relaxed in the soah (open area) to listen to their parents tell stories. The change from living in longhouses to single-family houses makes it impossible for the Dayak to continue the story telling tradition. There is simply not enough space in a single-family house for it.

The coming of radio and television has promoted a consumptive culture. This is the era of new colonialism by capitalism. Dayak youngsters migrate to Indonesian cities in great numbers, either to pursue their studies or make a living. They are enthralled with the glamour and lifestyle of urban Indonesians. Some drop out of school, lacking skills and knowledge, to pursue this lifestyle. This is the short cut attitude. In Pontianak, for example, dozens of Dayak girls, end up working the bars, karaoke joints and hotels.

Since the 1970s, the Dayak have been baffled by the existence of mining projects, logging by forest concessionaires, plantations and industrial timber estates. Socio-economic expert Mubyarto said the presence of the giant projects in Kalimantan changed the Dayak’s source of wealth.

The rattan monopoly has impoverished the Dayak in East and Central Kalimantan. The gold mining in Ampalit (Central Kalimantan ), coal mining in East Kalimantan and gold mining in Monterado (West Kalimantan) have caused the locals to suffer. The same thing has happened to the Dayak Bentian, Dayak Pawan-Keriau and Empurang. They struggle against the plantations, which are partly financed with foreign loans. They are forced to give their land to the investors. After the land transfer, all the plants, all the sacred places and cemeteries were demolished and replaced by palm oil trees. They are forced to pay the investors for the privilege of living on their own land in installments.

The project ruins the environment, as well as the social, cultural and political patterns. They have marginalized the sovereignty and dignity of the Dayak over the Land and natural resources.

src="http://pagead2.googlesyndication.com/pagead/show_ads.js">

Dayak population estimated at about four million spread over the four Indonesian provinces in Kalimantan / Borneo, the Malaysian territories of Sabah and Serawak and Brunei Darussalam. In Sabah, the Dayak are known as Kadazandusun.

In the past, anthropologists described the Dayak as the "legendary natives of Borneo" who lived in longhouse and engaged in head-hunting. Today, they form a small minority, the loser in an era of swift change and modernization.

The original Dayak identity their cultural, economic, religious and political life has been preserved through their oral tradition. Experts agree that there are many basic affinitives in the legends of the various Dayak groups. Sadly, though, all the original elements of Dayak life as described in the legends have suffered significantly from external elements.

Modern Religions

Christianity greatly affected the status of legends among the Dayak groups. The legends, which were recited during rituals, were dismissed as animistic. The Christian converts deem adherents to the traditional religion primitive and obsolete. The doctrine was spread through schools and sermons in the villages. In Central Kalimantan, people call it the "obsolete yeast" or "emptying glass" policy. Anthropologist J.J. Kusni concludes in one of his books that the propagation of Christianity amounts to the conquering of the Dayak.

The Christian proselytizers shouldering what they call ‘la mission sacre’ of civilizing the savage peoples see the Dayak culture as ‘obsolete yeast’, worth disposing. The ‘obsolete yeast’ concept tends to drain the Dayak of their culture and fill them out with new values," says Kusni. The policy was exercised not only in Central Kalimantan, but also in East, West and South Kalimantan. Further, Christianity was considered as a savior and a symbol of modernization. The impact has been great. The Christians are uncomfortable attending funerals and weddings of pagans.

In a West Kalimantan village, used as a base by a Christian mission, posters are plastered all over the place to intimidate Dayaks from practicing their cultural traditions. A poster in illustrates a path branching in two. The left is "the road to hell", with a picture of a ritual at the end of the road. The right is "the road to heaven", with a picture of modern life is seen at the end of the road.

Lifestyle

Before the 1950s, the Dayak peoples lived in communal longhouses. Today, longhouses are rare in Kalimantan. Their disappearance in turn affects the process of preserving the social, economic, cultural, and political values of the Dayak. Before, children were taught the basics, including the legends. Before going to bed, youngsters relaxed in the soah (open area) to listen to their parents tell stories. The change from living in longhouses to single-family houses makes it impossible for the Dayak to continue the story telling tradition. There is simply not enough space in a single-family house for it.

The coming of radio and television has promoted a consumptive culture. This is the era of new colonialism by capitalism. Dayak youngsters migrate to Indonesian cities in great numbers, either to pursue their studies or make a living. They are enthralled with the glamour and lifestyle of urban Indonesians. Some drop out of school, lacking skills and knowledge, to pursue this lifestyle. This is the short cut attitude. In Pontianak, for example, dozens of Dayak girls, end up working the bars, karaoke joints and hotels.

Since the 1970s, the Dayak have been baffled by the existence of mining projects, logging by forest concessionaires, plantations and industrial timber estates. Socio-economic expert Mubyarto said the presence of the giant projects in Kalimantan changed the Dayak’s source of wealth.

The rattan monopoly has impoverished the Dayak in East and Central Kalimantan. The gold mining in Ampalit (Central Kalimantan ), coal mining in East Kalimantan and gold mining in Monterado (West Kalimantan) have caused the locals to suffer. The same thing has happened to the Dayak Bentian, Dayak Pawan-Keriau and Empurang. They struggle against the plantations, which are partly financed with foreign loans. They are forced to give their land to the investors. After the land transfer, all the plants, all the sacred places and cemeteries were demolished and replaced by palm oil trees. They are forced to pay the investors for the privilege of living on their own land in installments.

The project ruins the environment, as well as the social, cultural and political patterns. They have marginalized the sovereignty and dignity of the Dayak over the Land and natural resources.

src="http://pagead2.googlesyndication.com/pagead/show_ads.js">

Comments

Post a Comment